Theo’s Daily Diary: The Perspective of a First Year on the Dig

Day 1: Monday 22nd May

As many of you will know, the first day of any seasonal excavation usually involves a lot (a LOT) of weeding and cleaning back of a years worth of debris! And our first day at Hartygrove was no exception (check out out Instagram instagram.com/bristol_archaeology/ for some amazing ‘Green to Clean’ transformations!). All three trenches were weeded and cleaned up in preparation for the archaeology to come!

Day 2: Tuesday 23rd May

Today we worked the trenches, trekking through the grassy fields after a long bus ride, we reached the medieval site of Hartygrove. Working there all of yesterday we knew what was to be done; so we set to work with little prompt. By trowelling around in the soil we managed to pull the soil from between the rocks. We brushed away the remaining dirt leaving the wall leaving fit for a photo of archaeological standard. Though this sounds like a simple task there were many challenges we had to overcome. Many people digging through nests of red ants, coming across startlingly massive spiders, including the false widow, the deadliest spider in the uk!

Though this was only part of our grilling work. Away from the shade and underneath the blazing sun, the other excavators were digging. Digging up the mud they worked together in a dynamic fashion, they quickly managed to locate many interesting artefacts, including animal bone and pottery.

Day 3: Wednesday 24th May

We kicked off today where we had left off from yesterday. With only a few changes, two of us had started to use the rover, a GNSS tracking device to measure some of the dimensions of the walls. The pair working with the device thought that it was a lot quicker than measuring and mapping out the dimensions of the wall as this does it automatically as you walk around. There were also people who had begun section drawing. This was exciting because it means that they have finally finished parts of their work on the excavation and can appreciate the done version before moving on, by measuring out the dimensions with a ruler.

More finds have been found today following on from pieces of oyster shell and broken pottery most likely from the medieval age. Though one incredible find came while clearing the rubble they came across a high status piece of pottery most likely from a wine pot, it was distinguished from the other finds because of its patterns along with its pretty green colour. With so many finds happening before the actual digging has begun, from just the gardening and clearing of rubble , many of the students on site are optimistic for what will be found.

Though the prospect of new technologies has got the students talking. Just before lunch break a drone was spotted flying in the air. Many students said they they were hoping to flying it.

However not all went off without a hitch, as students came back from their lunch break to a temporary water shortage! It was quickly resolved by two students trekking back up to the tap across two fields for a refill but lessons were learned – maybe the drinking water shouldn’t be used for cleaning finds.

Carry on reading as over the next few days I will write about my latest research on site and I interview staff and second years about last year.

Day 4: Thursday 25th May

A day of an excavator. We have seen many of the skills involved with excavations over the first few days. Most of us started with de-weeding, wearing thick gloves we pulled the overgrown plants from the area. Though the walls had been excavated last year dirt fallen into the cracks between the stone walls and plants had grown from the dirt leaving long roots all the way to the bottom. From that we began removing the rubble. Making constant trips back to dump our buckets full of spoil and wheelbarrows of stones. The trowel is bread and butter for an archaeologist, and in some cases they’re best friend. You can tell how experienced an archaeologist is by how attached they are to their trowel. It’s a great tool for removing the dirt from the rocks, digging out trenches, making the stratigraphic layers of the ground clearly visible and of course keeping you company when the conversation with your fellow excavators ends. In hard ground though a mattock can be a better option. Though less friendly it can do a quicker job than the trowel, when covering a larger area and precision is not as needed. Another important piece of equipment is the camera. When a feature has been properly excavated it needs to be recorded. How many archaeologists does it take to take a photo, in our latest case 6. One person to take the photo and another 5 to hold up a sheet above the site in order to make sure no shadows were captured in the image. No archaeologist would deny that the most exciting part of an excavation is finding something, though this only represents a small part of the time spent on a site, it is definitely the most memorable. Most finds are hard to tell apart from small rocks and can leave you eagerly studying each one, wondering if it’s in fact a piece of mid century pottery or slag, or just a small rock. Though there’s no better feeling than identifying a new feature or placing a find into the daily finds tray.

Day 5: Friday 26th May

As we came to work on Friday, we realised we there was still a find we were still hoping to see the whole of. Yesterday what seemed like the remains of an entire pot was found while removing rubble. If we didn’t manage to uncover it today we would have to wait until the next three days to uncover it, due to the THIRD May Bank Holiday. Of course we keenly tried to clear all of the nearby rocks removing them to see what we had found, an exhilarating prospect, as usually we may find a small bone or piece of pottery but finding a whole of an object is very rare. So by working speedily but being careful not to harm the find, we finally uncovered it. Work slowed though not because it was the end of the week, and many of us had the weekend in our minds, thinking about the three day holiday that awaited us, after we finished today. Instead it was to crowd around the now fully exposed pot. Murmuring around it one person even described it as ‘giving birth’. We look forward to hearing about Isotope analysis from the soil context and potential lipid analysis! Next week our Archaeobotanist Charlotte will be using a method called flotation to see if she can extract any charred floral remains! Keep your eyes and ears peeled for next weeks diary, and for project updates.

The National Lottery Heritage Fund is in place to connect people and communities with local and national heritage, and in partnership with this fund we are embarking on an exciting project! The South West Anarchy Research Project will build a bridge between the community and a variety of archaeological sub-projects, relating to the concept of ‘1000 years of Anarchy’.

The National Lottery Heritage Fund is in place to connect people and communities with local and national heritage, and in partnership with this fund we are embarking on an exciting project! The South West Anarchy Research Project will build a bridge between the community and a variety of archaeological sub-projects, relating to the concept of ‘1000 years of Anarchy’.

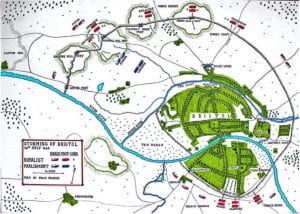

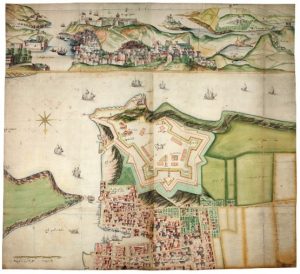

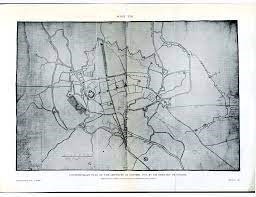

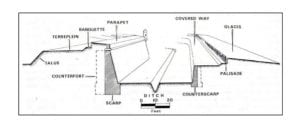

During these years of Civil War, what we see today as the historic environment changed drastically. Buildings all across the country were heavily fortified, be them castles or not, and many of the ruined castles that we see across the English landscape today were destroyed as a result of this catastrophic conflict.

During these years of Civil War, what we see today as the historic environment changed drastically. Buildings all across the country were heavily fortified, be them castles or not, and many of the ruined castles that we see across the English landscape today were destroyed as a result of this catastrophic conflict.

After the death of Charles I, Cromwell dominated the Commonwealth of England as a member of the Rump Parliament and was subsequently elected to command the English campaign in Ireland in 1649. His forces occupied the country and brought an end to the Irish Confederate Wars. Cromwell also led an attack against Scotland in 1650. In 1653, Cromwell dismissed the Rump Parliament, and set up a short-lived Barebone’s Parliament, and his fellow leaders invited him to rule as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England. Cromwell died of natural causes in 1658, and was succeeded by his son Richard, whose weakness led to the Royalist’s return to power and the re-establishment of King Charles II.

After the death of Charles I, Cromwell dominated the Commonwealth of England as a member of the Rump Parliament and was subsequently elected to command the English campaign in Ireland in 1649. His forces occupied the country and brought an end to the Irish Confederate Wars. Cromwell also led an attack against Scotland in 1650. In 1653, Cromwell dismissed the Rump Parliament, and set up a short-lived Barebone’s Parliament, and his fellow leaders invited him to rule as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England. Cromwell died of natural causes in 1658, and was succeeded by his son Richard, whose weakness led to the Royalist’s return to power and the re-establishment of King Charles II.

.

.

.

.