Since our excavation shed a new light into the Civil War history in Bristol, let’s have a look at the role that the city played in the war. The English Civil War was a series of battles between Royalists, who supported King Charles I, and Parliamentarians, who fought against him. The conflict surrounded the governance of England and religious freedom. King Charles and his supporters wanted absolute monarchy due to his strong belief in the divine right of kings, whereas the Parliamentarians wanted constitutional monarchy. The conflict ended with a Parliamentarian victory, marked by the execution of Charles I, the exile of his son, Charles II, and the abolition of the English monarchy. The English monarchy was then replaced by the Commonwealth of England, with Oliver Cromwell ruling over the British Isles.

The event that first triggered conflict was the dissolution of Parliament by Charles I in 1629, which marked the beginning of 11 years of Personal Rule- namely, a period of government without parliaments. In a bid to secure religious conformity across Britain, Charles introduced a new prayer book in Scotland, which resulted in protest from the Scots. Charles attempted to secure order by preparing to send troops to Scotland. However, this required money which Charles did not have, causing him to summon a new parliament. This parliament was resentful of the monarch’s domestic policies, refusing to grant him money, causing Charles to re-dissolve parliament a month later. Scotland’s forces overpowered the English, forcing Charles into a truce due to their occupation o f Northern England. Once again, Charles re-established parliament to provide him with financial assistance- a decision which backfired, with many members of parliament using their position to voice their complaints against Charles’s policies. In an attempt to demonstrate political control, Charles attempted to arrest five leading members of parliament. However, they evaded the monarch’s capture, and in 1642 the civil war began.

f Northern England. Once again, Charles re-established parliament to provide him with financial assistance- a decision which backfired, with many members of parliament using their position to voice their complaints against Charles’s policies. In an attempt to demonstrate political control, Charles attempted to arrest five leading members of parliament. However, they evaded the monarch’s capture, and in 1642 the civil war began.

Charles set up his royal standard in Nottingham, summoning his subjects to join him in the fight against parliament. Almost all of southern England fell under Parliamentarian control, with the exception of Cornwall, who became some of the king’s strongest fighters. On the 23rd of October 1642, Charles’s army advanced on London, resulting in a battle at Edgehill in Warwickshire which proved to be indecisive. The following September, after a series of reverses, Charles called for a ceasefire with the Catholic insurgents in Ireland in order for the English Protestant soldiers to return home and serve in the Royalist army. This caused even more outrage from the Parliamentarians, who then formed an alliance with Scotland, who agreed to fight in return for church reform in England. On the 2nd of July 1644, Prince Rupert’s army was destroyed in a battle with the Parliamentarians and the Scots, resulting in the loss of the north to the king. Following a defeat in the Battle of Lostwithiel in Cornwall, parliament passed the Self-denying Ordinance, requiring all members of parliament to lay down their commands. This restructured fighting force, which was made law on the 15th of February 1645, was named the New Model Army, of which Oliver Cromwell was second in command. This army went on to crush the Royalist’s main field army in Naseby, Northamptonshire, effectively crushing any chance of Charles winning the civil war.

On the 5th of May 1646, Charles surrendered to the Scots, who handed him over to the Parliamentarians. Two years later, in 1648, a second civil war broke out, with Royalist rebellions breaking out throughout the country. The Royalist force rode south, but were destroyed by Oliver Cromwell’s army, marking the end of the Royalist resurgence. On the 30th of January 1649, Charles was executed, after being found guilty of treason. In an effort to recover his father’s throne, Charles I’s eldest son made a bargain with the Scots. On the agreement that he take the Covenant himself, the Scots crowned him King Charles II of Scotland in early 1651. After his coronation, Charles II utilised his Scottish army to invade England. Despite the support of many English royalists, Charles II’s army was defeated in battle at Worcester by Oliver Cromwell’s forces. This was the last major battle of the English Civil War, and Charles was exiled abroad.

Following the execution of Charles I, there were a number of internal disagreements within parliamentary factions. To resolve this, Oliver Cromwell dissolved this rump parliament and summoned a new one, which also failed to manage the complex issues England was now facing. Cromwell also named himself ‘Lord Protector’, essentially giving him the powers of a monarch. His regime was supported by his continuing popularity with the military. In 1658, Oliver Cromwell died, and his son Richard took his position as Lord Commander. The Commonwealth fell into financial chaos and parliament was once again dissolved. Richard Cromwell was overthrown, and a leading officer of the army realised that the only end to the political chaos would be the restoration of Charles II. On the 29th of May 1660, Charles II was officially restored to the English throne, an event marked by massive celebrations.

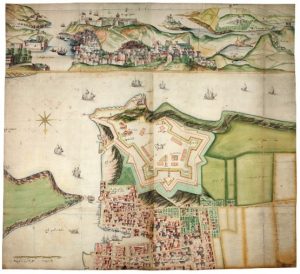

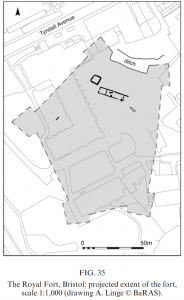

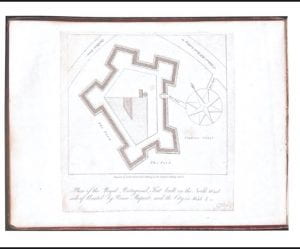

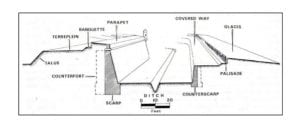

Bristol should have played a key part in the English Civil War due to the importance of the port to both the Royalists and Parliamentarians. However, it did not meet its expectations as a strategical key due to the population’s reluctance to participate in the war. Bristol’s governing body initially wanted to keep the city neutral, with a request being made in 1642 for Parliamentarian Thomas Essex to not occupy the city. Despite this, Essex’s forces managed to enter Bristol with little resistance due to its weak defences. For the duration of the war, the Royalists utilised Bristol as a receiving point for reinforcements from Ireland. Bristol Castle, as well as the Frome and Avon rivers, meant the town was well defende d against attack, but the population of Bristol were largely unenthusiastic in fulfilling the expectations of such a large and rich port town. The Royal Fort House, designed by Dutch military engineer Sir Bernard de Gomme, acted as one of Bristol’s strongest defences, as it was one of the only purpose-built defensive works of the era. The fort was made to be the western headquarters of the Royalist army, but it was demolished in 1655.

d against attack, but the population of Bristol were largely unenthusiastic in fulfilling the expectations of such a large and rich port town. The Royal Fort House, designed by Dutch military engineer Sir Bernard de Gomme, acted as one of Bristol’s strongest defences, as it was one of the only purpose-built defensive works of the era. The fort was made to be the western headquarters of the Royalist army, but it was demolished in 1655.

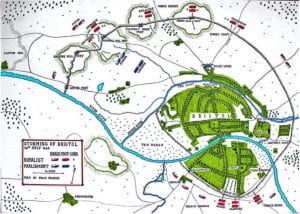

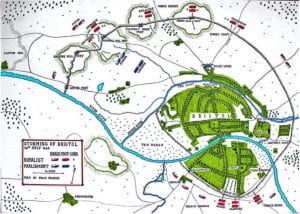

The key event that occurred in Bristol during the war was the Storming of Bristol by the Royalists in 1643, in which Prince Rupert’s army seized the town from its Parliamentarian garrison. Bristol went on to become a major supply base for the Royalists, as well as a centre for communication, administration, and manufacture. Bristol was important to the Royalists due to their dependence on foreign aid and imported weaponry. In order for them to receive this cargo, however, the ships had to evade Parliamentarian patrols. In September 1645, the second Siege of Bristol occurred, and the city surrendered to the Parliamentarian army. In disgrace, Prince Rupert fled England, and English Royalists were left with only the port of Chester to connect them to Ireland.

After the death of Charles I, Cromwell dominated the Commonwealth of England as a member of the Rump Parliament and was subsequently elected to command the English campaign in Ireland in 1649. His forces occupied the country and brought an end to the Irish Confederate Wars. Cromwell also led an attack against Scotland in 1650. In 1653, Cromwell dismissed the Rump Parliament, and set up a short-lived Barebone’s Parliament, and his fellow leaders invited him to rule as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England. Cromwell died of natural causes in 1658, and was succeeded by his son Richard, whose weakness led to the Royalist’s return to power and the re-establishment of King Charles II.

After the death of Charles I, Cromwell dominated the Commonwealth of England as a member of the Rump Parliament and was subsequently elected to command the English campaign in Ireland in 1649. His forces occupied the country and brought an end to the Irish Confederate Wars. Cromwell also led an attack against Scotland in 1650. In 1653, Cromwell dismissed the Rump Parliament, and set up a short-lived Barebone’s Parliament, and his fellow leaders invited him to rule as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England. Cromwell died of natural causes in 1658, and was succeeded by his son Richard, whose weakness led to the Royalist’s return to power and the re-establishment of King Charles II.

.

.

.

.